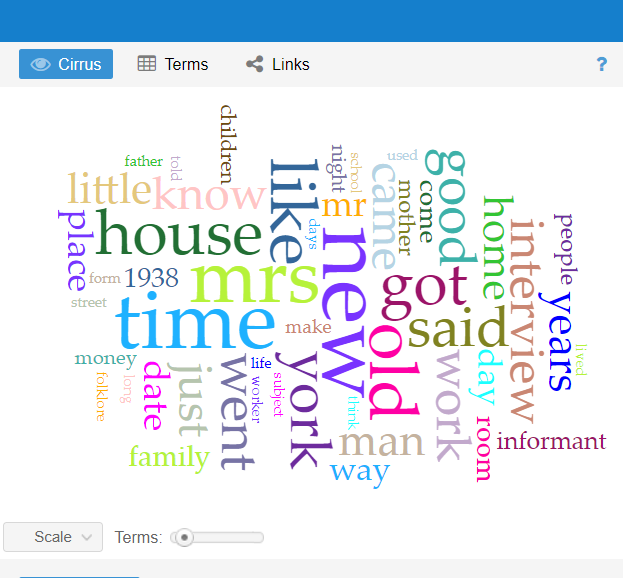

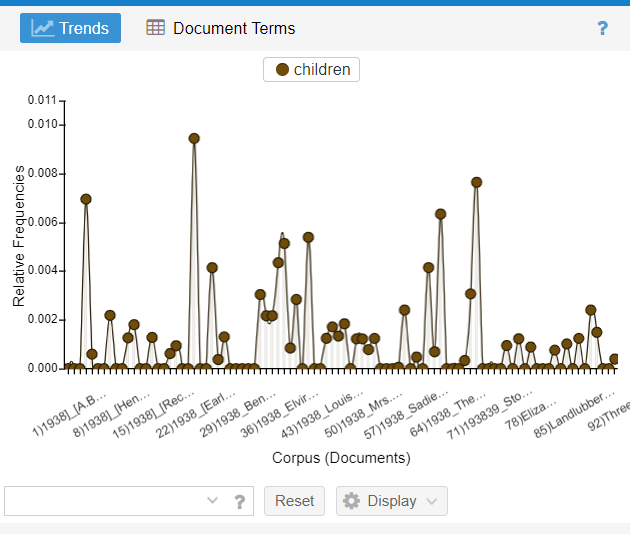

In examining the entire semester and the different topics we touched on as a class concerning the 1930’s, I found myself constantly going back to the idea of how FDR’s New Deal was to sort of be the reprisal of the America that existed before the Great Depression, (at least in terms of pride). But in thinking about that, I began to question how “great” that America really was, and if the New Deal was any better, and I realized it would probably depend on who you asked. America has never and still is not completely 100% equal for all, and it 100% was not equal during the 1930’s, at least in terms of the lives of black and white Americans. That being said, I decided to formulate my final exhibit question around this concept by asking “How was 1930’s America different for white and black people?”. I examined this question by utilizing certain skill assignments that we had used during the semester such as image annotation 1, story mapping, and glitching. I felt that these three skill assignments best corresponded with the topics I was going to more closely analyze which were the differences in art, everyday life, and travel. Each skill assignment allowed me to go more in depth with my analysis than I had previously thought I would be able to.

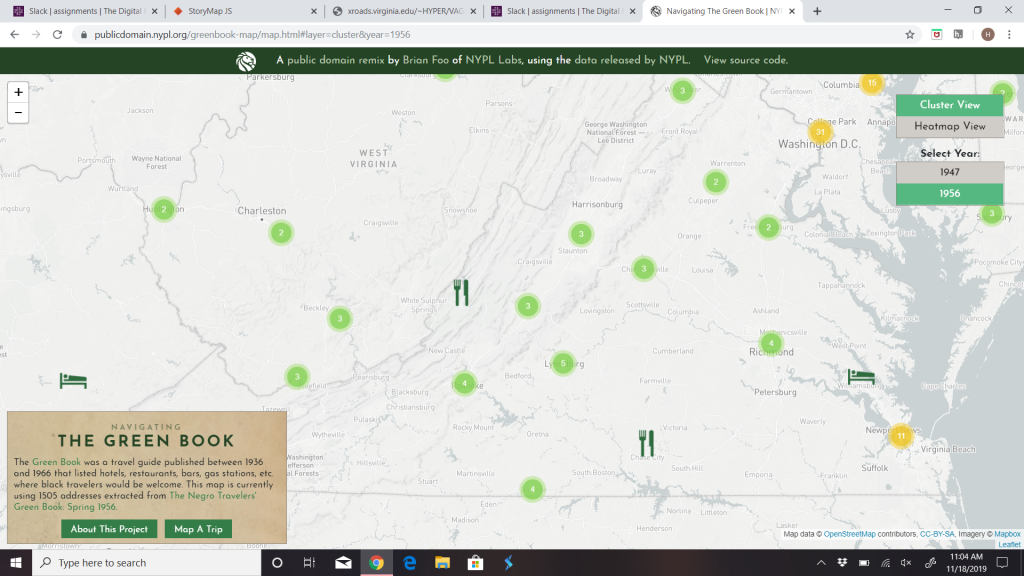

While doing this final exhibit, I was able to reflect more regarding the actual history of the 1930’s and how all the skill assignments we learned this semester actually helped me learn all of the things that I did. It helped me gain a better understanding of the impact that digital technology has, and how as ethical digital citizens, we have a duty to use technology and the information on it responsibly. For example, had it not been for the glitching article 2, I wouldn’t have been able to draw the conclusions I did regarding Augusta Savage, and the glitched image that I included in my final exhibit. In my final exhibit I also included a storymap that mapped a trip from New York to Missouri, and to do that I had to utilize the “Navigating the Green Book” project 3 so I could determine what stops an African American traveler would make during that time. All of these things, when utilized correctly, transform history and the ability to understand history, into a more modern thing. As a viewer, as a student, when you interact with history while using technology and new platforms you may have not previously known of before, you’re forced to get a better understanding of the content because you are actively interacting with the content. It’s far different from just reading a textbook or article about it. But with that ability to interact more with history through the use of technology, comes the responsibility of being professional and ethical when doing so. For our lecture on Digital Citizenship, we read an article about how a George Mason University professor had his students create a hoax on wikipedia 4 and that alone sparked outrage, even though it was a lighthearted assignment. So if anything this just cemented more the idea that what you say or do and how interact with online digital content is extremely important. Everyone needs to be ethical and responsible so as not to spread false information. In a general sense I feel like the more that digital humanities becomes a bigger place for scholarship and the more that people actually take digital humanities seriously, the more that we will see conversations concerning digital citizenship in the news.

In all, my ideas regarding digital humanities and 1930’s history have evolved and grown because of this course. By combing history with digital projects, I was able to interact more with the content I was learning, and able to gain a better understanding of both digital humanities and history all at once. Through using the two, I was able to formulate broad historical questions, and then closely analyze those questions with each skill assignment we were given. This course provided me a better grasp of the history of the 1930’s, but more so than that, it provided me with new resources that I will be able to utilize in future project and scholarship to come.