Final Project: http://jessicadoeshistory.com/cnd/exhibits/show/moving-on-up

Ever since we started learning about the different departments of the Cultural New Deal, I have been captivated by the idea of mobility. Throughout all of the New Deal, something was moving, something was happening and the people greatly benefitted from it. 1People came together and got things done. What really tipped this off for me was when we watched “It Happened One Night” for homework. There are so many examples of mobility within that movie that even I got excited or had to dance along to the music.

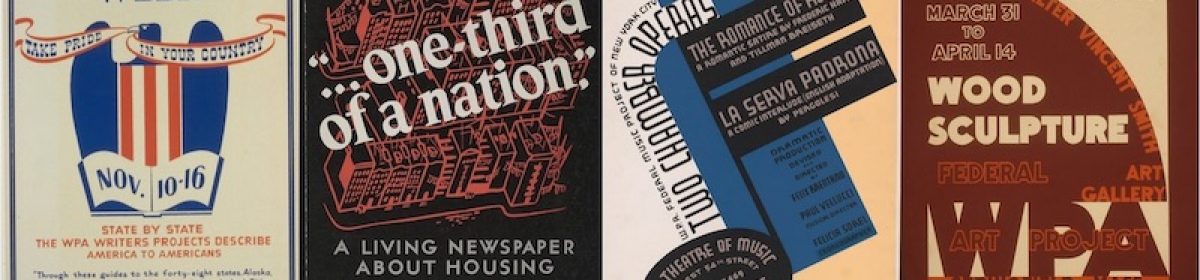

To me, this project was reminiscent of a 5-paragraph essay, so I handled it that way. I focused my argument around mobility being a major theme and result of the New Deal. I wanted to study the Federal Art Project as well, but I mostly just kept it to the Federal Writers Project, the Federal Music Project, and the Federal Theatre Project. Each one of them provided movement in a unique way.

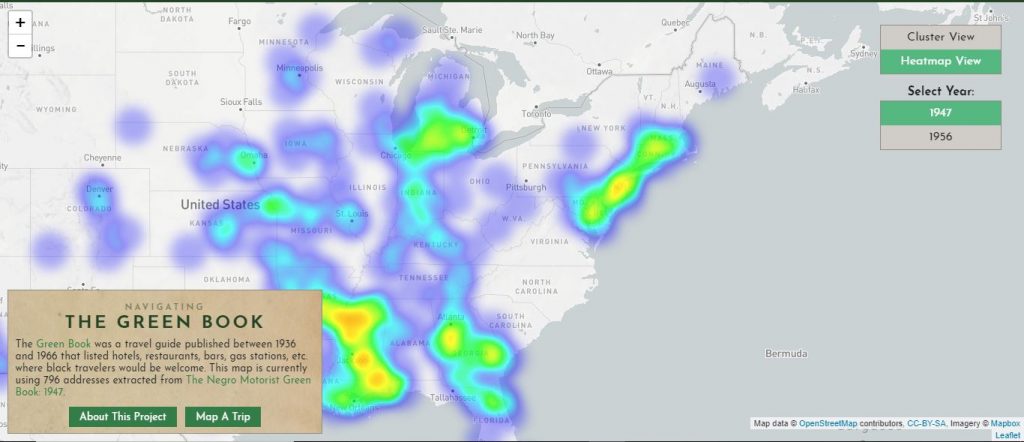

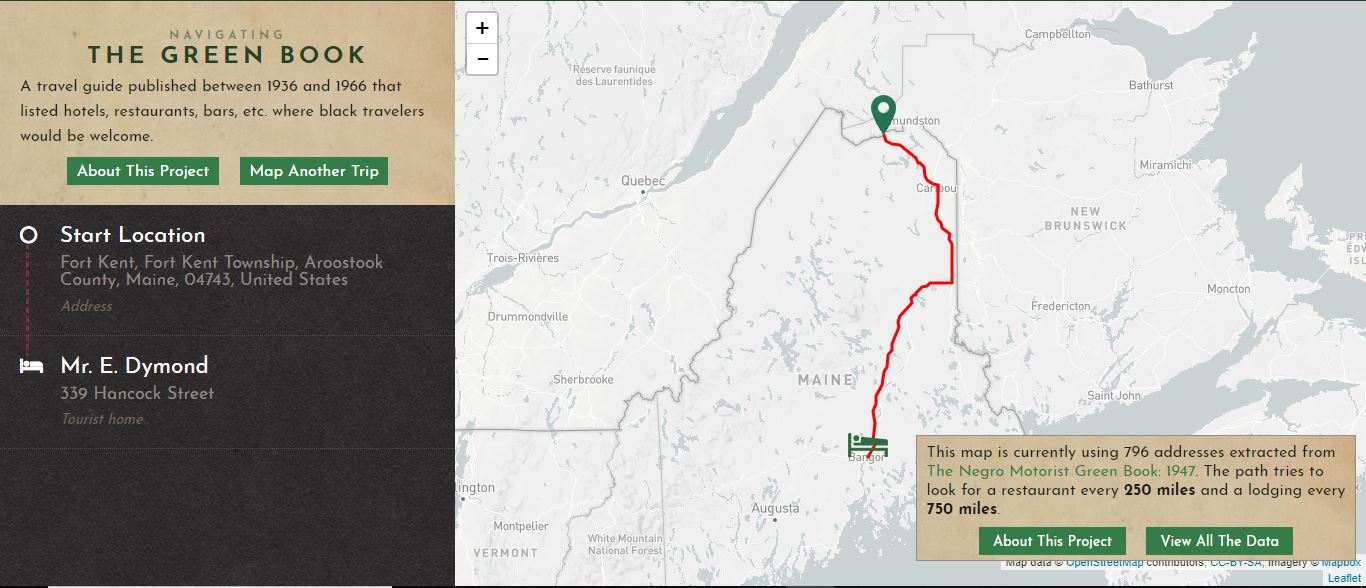

The Federal Writers Project focused on making the American Guides series to help establish what a new America would look like coming out of the Depression. The guides would be a tool to codify what the nation now is and be emblematic of American patriotism. 2 To me, the tours got people moving and exploring and figuring out what America would be like. I focused on the touring aspects of the guides, specifically in Maine, discovering that some of the tours went through wilderness. I conveyed this through a story map, showing how the tours were not cyclical, but more linear, running predominantly in the cardinal directions. Using the map helps clarify the distance and vastness of the land covered.

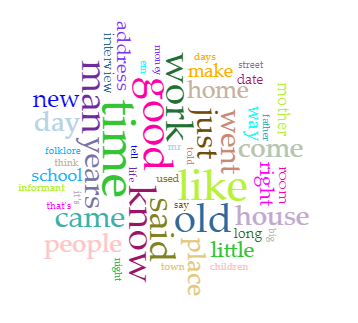

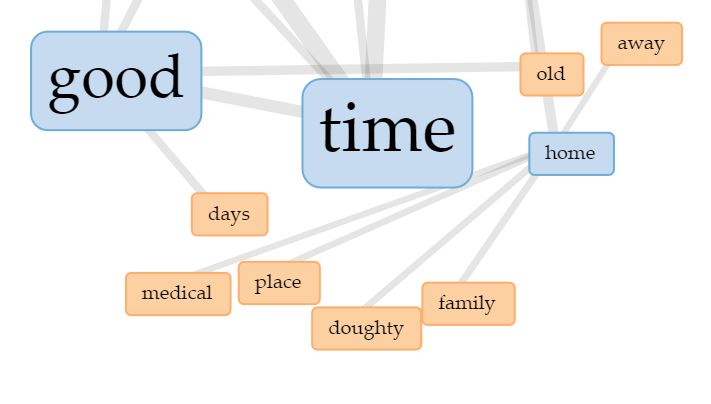

The Federal Music Project, is, to me, the best project out of the four. I find it simply amazing all the songs they were able to collect and create. The way the FMP got people moving was through the gathering of folk songs. These became emblematic of American roots and where people came from, permitting a mixture of cultures. It provided entertainment for the American people and traveled with them when they eventually joined the war in 1945. It was able to thrive like this because it held no political partisanship. 3 There were not many high-profile figures in the FMP machine, just normal people wanting to make and collect music. For this project, the obvious choice was soundcite. With it, music and words can harmonize and good ideas can be generated. I mostly used it to show emotion that evoked movement or the desire to join in and sing.

The Federal Theater Project, complete opposite of the situation in the FMP, was very high-profile with the risk-taking Hallie Flannagan at the helm. Much of the movement the FTP brought came in the form of theater shows which shook up society. A great example of this is Orson Welles’s “Macbeth,” 4his debut stage play. It was a radical idea having African-Americans in major roles of Shakespeare as well as changing the location of the work. People gave it the connotation of “voodoo” thanks to this. The play got the gears moving for the FTP, bringing in lots of revenue. For this one, I used Omeka’s annotation feature to look at an image from Macbeth. I used it to explain how this was an up-and-coming time for various ethnicities, and African-Americans were finally being brought to the limelight of the stage. The movement here is the lifting up of others.

Much of the technology I used in this project is great. I feel that it can really help bring to light certain aspects of history we might be unable to see from just a cursory glance or reading. We, as digital historians, are able to look deeper into the subject and draw out new ideas to get a new perspective on things. Before this class, I barely knew much about the New Deal, but now I see the real breadwinner programs that helped solidify American culture. Trends like comics and social security still persists to this day, even the idea of popular “pop” music which resonates with the people. Ideas being remixed

5 for future use, like many of the songs Lomax collected are reused by modern day rap and hip-hop artists. 6 I hope to carry all this knowledge with me into future courses here at school.

This image, screenshotted from Google Maps shows the general path of the Fort Kent-Mattawamkeag Tour. While traversable today, White Americans would most likely have enjoyed the thrill of the sporting events (hunting game and fishing) and taking to the wooded trails and canoeing.

This image, screenshotted from Google Maps shows the general path of the Fort Kent-Mattawamkeag Tour. While traversable today, White Americans would most likely have enjoyed the thrill of the sporting events (hunting game and fishing) and taking to the wooded trails and canoeing.  This map, created from

This map, created from