Archives contain data meant to be kept forever, documents and photos and other things that researchers place enough stock in to warrant preservation. Obviously, scholars place value in archives– if a piece of data is in an archive, then by definition it must hold some use– but when I thought about how the general public would access archives, the utility grew murkier. I suppose that this is an archive’s chief mission: to appeal to the public so it can get the donations it needs to survive. The archivist for George Mason University’s special collections explained that her archive relies on donors.

The stark processing priorities surprised me very much from the “archival work [requiring] an ethics of care for the deeply personal and the deeply political” Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez espoused. What was most shocking is that sometimes, data donations are not always wanted for the archive. They are accepted because the donor has generously donated money, but mostly, they are irrelevant. An archive’s information is not just the biggest open books in the world, I discovered, but it is beholden to donors and just what data is actually available.

What archives digitise– the information deemed valuable enough to really be available for the general public, not hidden in basement boxes only to be seen by tenacious literati– is limited, too, often just for copyright issues. Thus, most of the digitised items are non-copyrighted photos. It made me realise just how much data I’ve yet to expose myself to. Most of my primary source research is done digitally, and when I found out just how few primary sources are realistically able to be digitised, I wondered about the limitations of some of my most ordinary research; in other words, “Who gets to be remembered and historicized by way of record creation? Who is forgotten or purposefully silenced in history by way of omission or destruction of records? How are records themselves… used to communicate misguided notions of holistic representation, truthfulness, neutrality, and objectivity?” 1

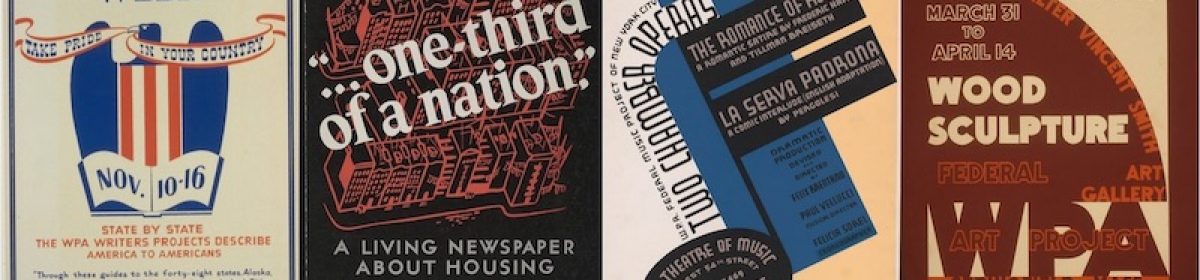

Our examination of the real data provided me with context for the period, what it would feel like handling these materials. Before, the Federal Theatre Project existed as a vague notion in my head, but the plethora of physical data we interacted with tethered that notion to earthly materials. It shouldn’t have mattered as much as it did, but I found another dimension added to my mental picture of the Federal Theatre Project, considering what these data would be like with the awareness and physicality of objects directly around me. The documents themselves that I looked into helped me understand just what “the integration of the theater with community life in the smaller communities” meant (before it became a ‘secondary air’), painting a picture of mobile theatres and the incredible innovations people put out. The documents helped me feel the elation of those government officials trying to stretch their craft to the American hinterlands, and clued me into what might’ve been frustration when FTP officials “encountered ignorance and intransigence when they made their ‘courtesy calls’ on state administrators.” 2

- Padilla, Thomas, and Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez. “Bias, Perception, and Archival Praxis.” Dh+lib, 13 Sept. 2017, https://acrl.ala.org/dh/2017/09/13/archivalpraxis/.

- Brown, Lorraine. “Federal Theatre: Melodrama, Social Protest, and Genius | Articles and Essays | Federal Theatre Project, 1935 to 1939 | Digital Collections | Library of Congress.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-theatre-project-1935-to-1939/articles-and-essays/federal-theatre-melodrama-social-protest-and-genius/. Accessed 12 Nov. 2019.