The Special Collections Research Center has archives full of data. Specifically, they put on display for us artifacts concerning the Federal Theatre Project (FTP). Across the tables lay various documents and objects. These objects and documents are very important as they help paint a picture, help develop the story of the FTP from what we, as scholars, already know. Scholars can take this information and rearrange to make varying arguments. Where the general public is concerned, I feel they are the consumers of the stories archivists make with their collection. Say, the archivists sits out a puppet, some pictures of dancers and notes on their designs. The public would interpret it however the archivist would set it up, and then begin to question or look into it further if the collection intrigues them. In this way, the archivists educate both scholars and the general public. The scholars being able to take the research a step further, while the public, I feel, would consider it more of a “national memory” or a facet of the past that greatly exemplifies the nation of the time.

The job of the archivist is to organize the data in any way they deem fit or suitable. When it comes to digitizing, there are two categories of how the item is interpreted: one is informational, the other is artifactual. Informational concerns the fixity and validation of the data or artifact. Does the information conveyed by the data remain the same as the artifact becomes digitized? Artifactual concerns interpretation. The archivist takes into consideration the materiality of the object. For example, in Artifactual Elements Pt. 1 1, the focus is on born-digital data being recovered from old-fashioned hardware. The archivist takes into consideration how data is stored, created and processed using this hardware. Then they consider the “environment” of the information and how that impacts how the source was created, altered or access. Desktops impact how we create and store records on our computer by a fixed screen. Another and final thing to consider is how word processing software, image editing programs, or how even operating systems can impact how contemporary records creators produce creative works.

Archivists struggle with trying to keep the meaning of their collections when digitizing them. Oft times, what is lost are the sensory perceptions. When you digitize an object, you can no longer smell it or feel it. All you can do is look at it interpretively and use various digital tools to analyze it that way. An Archivist, in this case, may prefer to digitize documents or pictures because a lot of the information can still be conveyed–digitally altered even. A three-dimensional object relies heavily on being “3-D.” When you digitize it, that already takes away its depth and makes it flat. You even lose the sense of touch which could key into how the object was made. Even though they are great to marvel at, these images and objects are subject to their own biases of the time. When we digitize them, that bias is carried forward through time. The scholar takes the time to parse through this bias and figure out who or what was omitted in order to get a good idea of the history being conveyed. 2 Simply, once these sources enter the digital world, many more challenges arise.

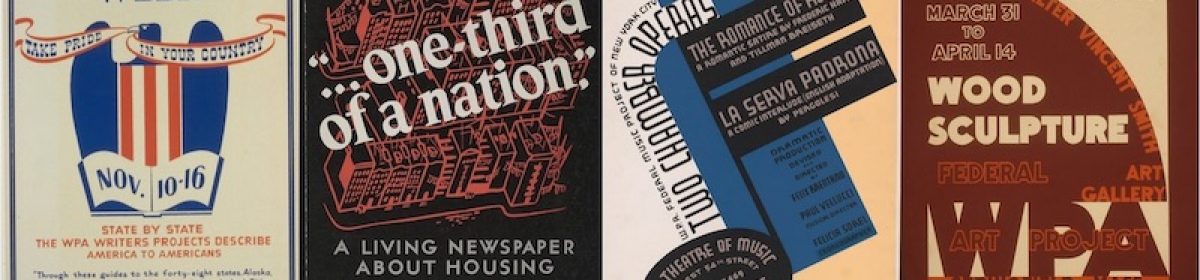

The SCRC FTP collection we saw involved a puppet, diorama and various forms of documentation. A lot of what they had put what we learned about the FTP into context. My group specifically got to see the Vaudeville and Negro Unit’s plays, stages, and costumes. In class, we discussed how the FTP did not use a lot of money for spending, but on salaries.3 The images painted a different story for me. Everything looked so lavish and exciting, made me wish I could have seen the pictures in their original context; rather, I wish I could see all the colors and see all the dramas in actions.