Does politically influenced music polarize or unite? More specifically, was the impact of politically influenced folk music in the 1930’s a polarizing or uniting factor? From slave songs sang in the fields to politically influenced raps heard on the radio, music has been and remained a prevalent form of expression used to convey personal struggles in a way that others can relate to. Mary Sullivan’s “Sunny California” is a story of a migrant worker leaving Texas to find work in California, a story many Americans found solidarity in at the time. It shares the struggles of homeless dust bowl migrants left out in the rain, their optimism washed away with their“rag houses”

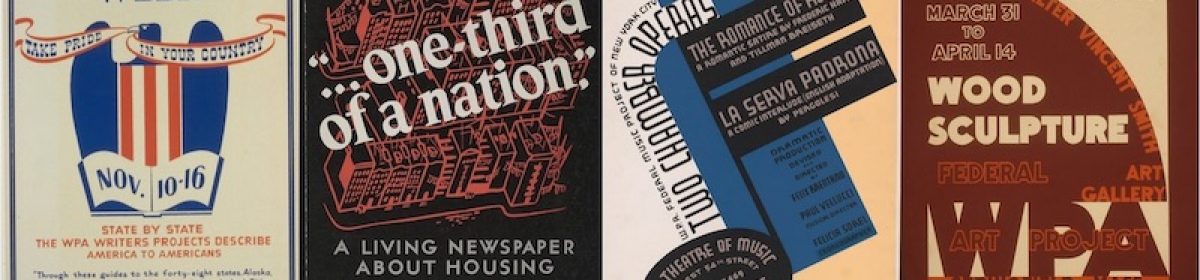

“Sunny California” shares a perspective not uncommon to the many destitute migrant workers suffering the economic effects of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. Music like Mary’s was a way to relate to another, to share in their struggles and try to find relief through community. Mary’s experience was collected as a field recording at the Shafter FSA Camp in 1941. She shares in the recording that she wrote the song four years prior, when she arrived in California. The Federal Music Project did the important work of collecting these narratives through the form of folk music, to preserve traditional music, and unintentionally stirring a pot of controversy when music was composed for the purpose of expressing political dissent.1 Like today, the country was politically polarized, and was brought together through music that spoke to common experiences.2

Musicians in the 1930’s sought to create ways that they could express their experiences in the changing times, in a way that the masses experiencing the same struggles could identify with and come together either for relief or for change. This hope perseveres today for modern musicians who strive to create music that people can find refuge in and be encouraged to action together. In regards to his most recent album, artist Hozier says, “I wanted to write a song that was hopeful and grounded in solidarity, grounded in love, in what can be achieved though organization, through the common respect of the dignity of people. It was the decision to write something that was not cynical, when it was so easy to write something that kind of rolled its eyes at global politics.”3

This perspective, in conjunction with Mary Sullivan’s, shows that even without placing blame or cynicism, and perhaps most effectively when done this way, politically influenced music can unite people through the expression of shared experiences and struggles. In this way, music can help work towards healing a nation.