Creating this map was a very interesting experience. Reading the book was quite difficult as the print was very small and it just wasn’t what I expected. Most modern guide books have a lot more notable tourist attractions, these books didn’t seem to exactly do that. Yes they went into the history of the town and area, but they give little recommendations on what to do there or what there was to see.

Although this assignment wasn’t exactly what I was expecting it definitely was a very interesting learning experience. I definitely agree with Sarah Bond after doing this project. Mapping these historical locations or any point of historical importance can be extremely useful for preserving and teaching history. If anything, these maps are becoming even more important as some of these locations no longer exist due to various causes.

Mapping and Spatial history are extremely important when developing land, by having access to these primary sources we can be able to tell if the land needs to be assessed by an archeological team first to preserve the history of the land. I believe this important skill can really help us to avoid situations that many European countries often face when building. Often times we hear of European countries accidentally unearthing historical site and destroying some very interesting finds, I believe more interest in spatial history and mapping primary sources could prevent that in the United States.

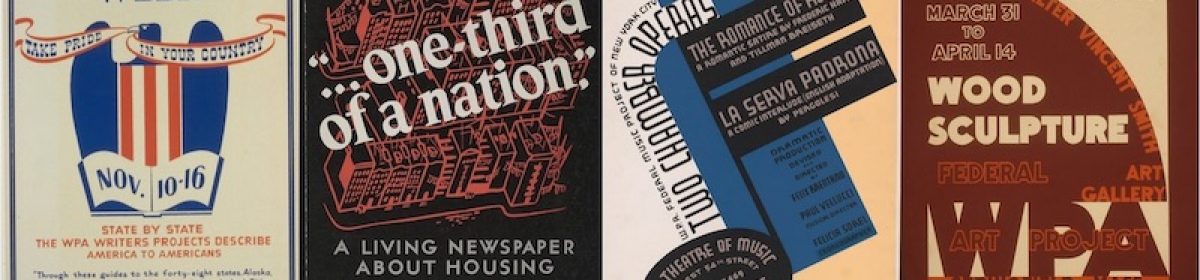

The projects encased in the Green Book collections are only the tip of what we could accomplish with the plethora of primary sources we have. People could even make these maps with online tools like I had done for this assignment. Of course the maps made by the people on the Green Book Project (as seen above) looked much better compared to mine.

The Green Book version of my tour definitely looks more professional then mine and didn’t take the exact path I did, but both versions could be useful. There was one thing I did notice while looking over the Green Books maps though, there was a lot of segregation going on during the times these were made. Most guide books probably won’t take into account that fact and would most likely cater to white Americans.

Travel must have been so much more difficult for people of color during that time. I never even thought about that possibility until I looked over these maps. It really goes to show how different things were back then. Of course black and white travelers could probably take the same route but they might not have been allowed in the same restaurant or get the same quality of service where they went.

That is another reason I appreciated the opportunity to look at the Green Book project, it opened my eyes to that factor. That is something I never would have noticed without looking at those maps, and I think it’s important to recognize the struggles people went through and learn from them. That way we don’t end up repeating the past.

Citations:

Bond, Sarah. “Mapping Racism And Assessing the Success of the Digital Humanities.” History From Below, October 20, 2017. https://sarahemilybond.com/2017/10/20/mapping-racism-and-assessing-the-success-of-the-digital-humanities/.

“ILLINOIS A DESCRIPTIVE AND HISTORICAL GUIDE : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. A.C.MCLURG & CO., January 1, 1970.

“NavigatingThe Green Book.” Navigating The Green Book. Accessed February 1, 2020. https://publicdomain.nypl.org/greenbook-map/.