I have had a few takeaways from this course that will stick with me for a while. They were further emphasized in this skill assignment. Based on previous work in the course, I understood that historical artifacts do not last forever, and their absence and destruction is often notably silent. There were several stops on my tour that no longer existed, despite their historical relevance, and are not even honored with a plaque. Especially as a native of the Washington, D.C. area, I was surprised to hear what used to be considered a tourist attraction. Additionally, I’ve developed an understanding that individuals experience history differently based on their experiences, and the use of the Green Book as a resource enhanced this point. My mapping project can be found here.

The first thing that caught my eye about this project as the transient nature of historical sites in the Washington D.C. area. Among the ten locations marked in my map, the Hoover Airport, Mount Eagle, and Fort O’Rourke have all been demolished. In historical context, not that much time has even passed since these sites were relevant to the culture. They were considered destinations to visit less than a hundred years ago, and each of the sites was established less than three hundred years ago. Given the rapid expansion and modernization of this area during the 20th century, it makes sense that each of these sites were replaced with government buildings, transportation infrastructure, and housing. This also made me consider how historical artifacts will be treated in our new digital age. The nature of historical research is undoubtedly changing1 If something doesn’t take up physical space, but space on a hard drive, is it more likely to be saved? And how do we determine what is worth saving? The Hoover airport wasn’t a commercial necessity. It became obsolete and unnecessary when more airports were established in the area. Why would it be worth maintaining?

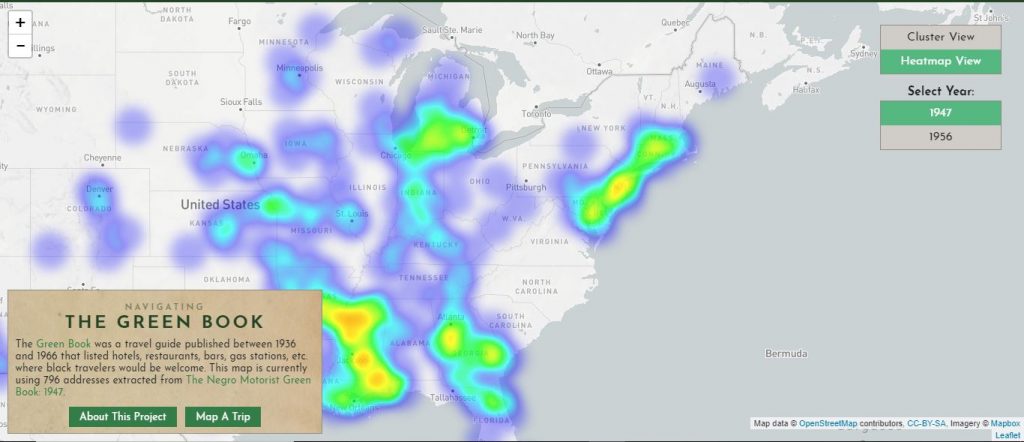

Alternatively, I also considered the role of diversity and perspective in historical preservation and tourism. In the first heat map I developed for this area, there were zero establishments that were marked as being welcome for African American travellers.

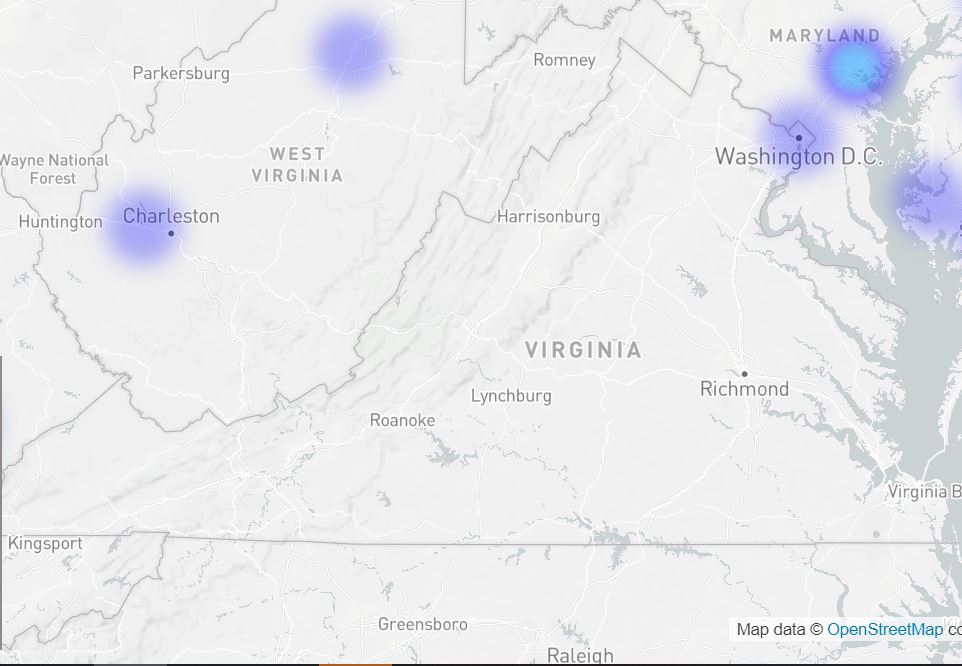

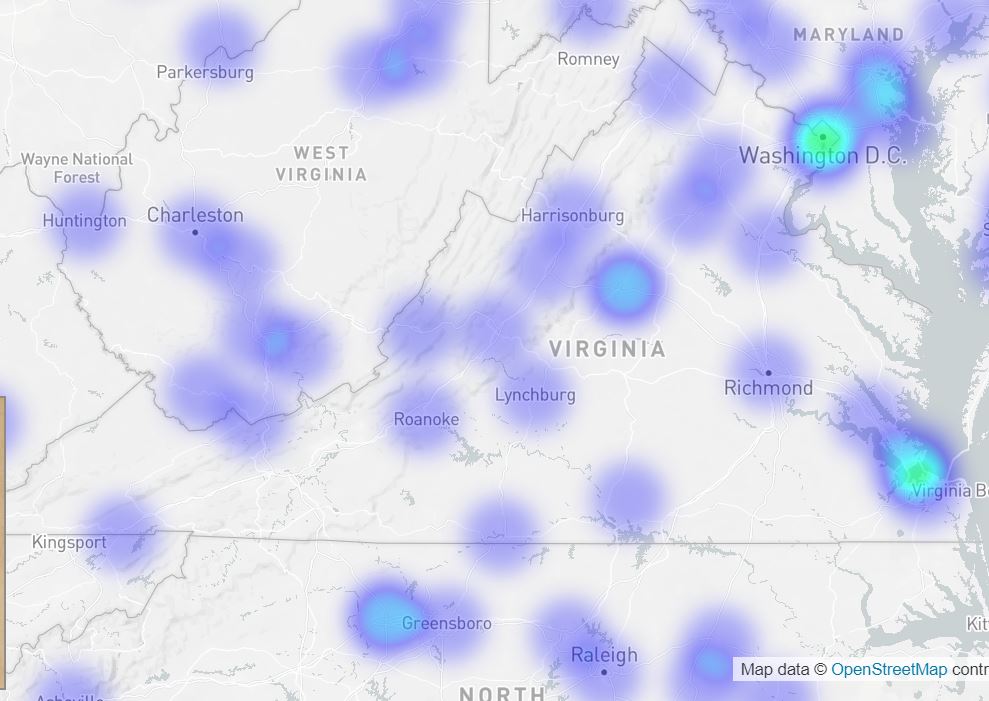

Although, this did improve in the succeeding decades. The above map shows information from the 1947 Green Book, while the below map shows information from the 1956 Green Book.

Still, this map is effective, as maps often are2, in helping to visualize and understand the reality of an individual’s existence. That first map portrays the uncertainty that any African American would have regarding tourism in Virginia.

Still, through the destinations provided, it becomes clear that African Americans are not a considered demographic for this guide. Despite discussions of three different plantations in this tour, there was zero discussion of enslaved people, but plenty of discussion about the architecture of said plantations. The focus on these plantations also leads to a situation where, if you’re an African American who doesn’t wish to visit the sites where people were enslaved and tortured for having the skin color that you currently have, the tour becomes unenjoyable.

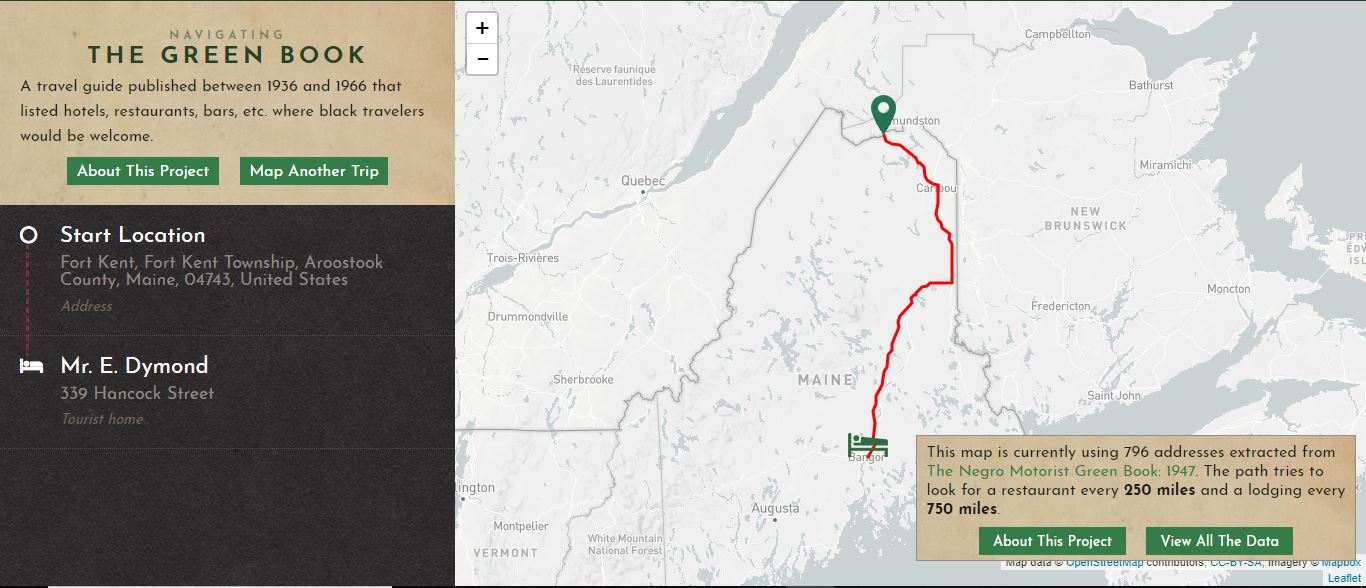

This image, screenshotted from Google Maps shows the general path of the Fort Kent-Mattawamkeag Tour. While traversable today, White Americans would most likely have enjoyed the thrill of the sporting events (hunting game and fishing) and taking to the wooded trails and canoeing.

This image, screenshotted from Google Maps shows the general path of the Fort Kent-Mattawamkeag Tour. While traversable today, White Americans would most likely have enjoyed the thrill of the sporting events (hunting game and fishing) and taking to the wooded trails and canoeing.  This map, created from

This map, created from